Summary

In episodes 12 and 13, Kelley Richey and Julia Avery discuss facts, debunk common myths regarding mass incarceration in the United States, and present ideas for incarceration alternatives.

Introduction

Although crime rates have steadily declined over the past 20 years, incarceration rates have somehow increased by 700% since the 1970’s. With America in the lead for mass incarceration, there is a dire need for us all to evaluate the data and reassess the way we handle crime. The evidence proving the damaging impact on inmates, their friends and family, U.S tax payers and more, is overwhelming.

5 Common Myths

Before getting into the data, here are five common myths along with their explanations. These are from Prison Policy Initiative’s article on Mass Incarceration.

1. Releasing “nonviolent drug offenders” would end mass incarceration.

It’s true that police, prosecutors, and judges continue to punish people harshly for nothing more than drug possession. Drug offenses still account for the incarceration of almost half a million people, and nonviolent drug convictions remain a defining feature of the federal prison system. Police still make over 1 million drug possession arrests each year, many of which lead to prison sentences.

Drug arrests continue to give residents of over-policed communities criminal records, hurting their employment prospects and increasing the likelihood of longer sentences for any future offenses. Nevertheless, 4 out of 5 people in prison or jail are locked up for something other than a drug offense — either a more serious offense or an even less serious one.

To end mass incarceration, we will have to change how our society and our justice system responds to crimes more serious than drug possession. We must also stop incarcerating people for behaviors that are even more benign.

2. Private prisons are the corrupt heart of mass incarceration.

In fact, less than 9% of all incarcerated people are held in private prisons; the vast majority are in publicly-owned prisons and jails. Some states have more people in private prisons than others, of course, and the industry has lobbied to maintain high levels of incarceration, but private prisons are essentially a parasite on the massive publicly-owned system — not the root of it. Nevertheless, a range of private industries and even some public agencies continue to profit from mass incarceration.

Many city and county jails rent space to other agencies, including state prison systems, the U.S. Marshals Service, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Private companies are frequently granted contracts to operate prison food and health services (often so bad they result in major lawsuits), and prison and jail telecom and commissary functions have spawned multi-billion dollar private industries.

By privatizing services like phone calls, medical care and commissary, prisons and jails are unloading the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people and their families, trimming their budgets at an unconscionable social cost.

3. Prisons are “factories behind fences” that exist to provide companies with a huge slave labor force.

Simply put, private companies using prison labor are not what stands in the way of ending mass incarceration, nor are they the source of most prison jobs. Only about 5,000 people in prison — less than 1% — are employed by private companies through the federal PIECP program, which requires them to pay at least minimum wage before deductions. (A larger portion work for state-owned “correctional industries,” which pay much less, but this still only represents about 6% of people incarcerated in state prisons.)

But prisons do rely on the labor of incarcerated people for food service, laundry and other operations, and they pay incarcerated workers unconscionably low wages: our 2017 study found that on average, incarcerated people earn between 86 cents and $3.45 per day for the most common prison jobs. In at least five states, those jobs pay nothing at all.

Moreover, work in prison is compulsory, with little regulation or oversight, and incarcerated workers have few rights and protections. Forcing people to work for low or no pay and no benefits allows prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people — hiding the true cost of running prisons from most Americans.

4. People in prison for violent or sexual crimes are too dangerous to be released.

Particularly harmful is the myth that people who commit violent or sexual crimes are incapable of rehabilitation and thus warrant many decades or even a lifetime of punishment. As lawmakers and the public increasingly agree that past policies have led to unnecessary incarceration, it’s time to consider policy changes that go beyond the low-hanging fruit of “non-non-nons” — people convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. If we are serious about ending mass incarceration, we will have to change our responses to more serious and violent crime.

Recidivism data do not support the belief that people who commit violent crimes ought to be locked away for decades for the sake of public safety. People convicted of violent and sexual offenses are actually among the least likely to be rearrested, and those convicted of rape or sexual assault have rearrest rates 20% lower than all other offense categories combined. More broadly, people convicted of any violent offense are less likely to be rearrested in the years after release than those convicted of property, drug, or public order offenses.

One reason: age is one of the main predictors of violence. The risk for violence peaks in adolescence or early adulthood and then declines with age, yet we incarcerate people long after their risk has declined. Despite this evidence, people convicted of violent offenses often face decades of incarceration, and those convicted of sexual offenses can be committed to indefinite confinement or stigmatized by sex offender registries long after completing their sentences.

And while some of the justice system’s response has more to do with retribution than public safety, more incarceration is not what most victims of crime want. National survey data show that most victims want violence prevention, social investment, and alternatives to incarceration that address the root causes of crime, not more investment in carceral systems that cause more harm.

5. Expanding community supervision is the best way to reduce incarceration.

Community supervision, which includes probation, parole, and pretrial supervision, is often seen as a “lenient” punishment, or as an ideal “alternative” to incarceration. But while remaining in the community is certainly preferable to being locked up, the conditions imposed on those under supervision are often so restrictive that they set people up to fail.

The long supervision terms, numerous and burdensome requirements, and constant surveillance (especially with electronic monitoring) result in frequent “failures,” often for minor infractions like breaking curfew or failing to pay unaffordable supervision fees. In 2016, at least 168,000 people were incarcerated for such “technical violations” of probation or parole — that is, not for any new crime.

Probation, in particular, leads to unnecessary incarceration; until it is reformed to support and reward success rather than detect mistakes, it is not a reliable “alternative.Expanding community supervision/High cost of low level offenses

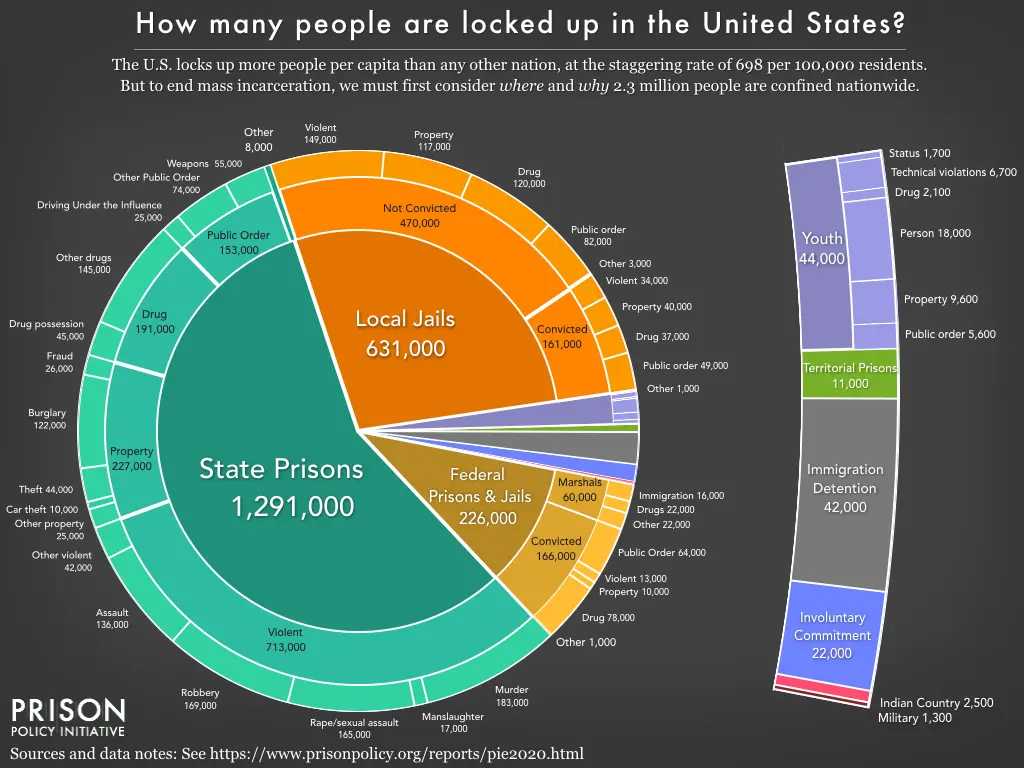

The “Whole Pie”

- Despite making up close to 5% of the global population, the U.S. has nearly 25% of the world’s prison population.

- The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people.

- The amount of correctional facilities and prisons far outweigh mental health and rehabilitation facilities:

- 1,833 State Prisons

- 110 Federal Prisons

- 1,772 Juvenile Correctional Facilities

- 3,134 Local Jails

- 218 Immigration Detention Facilities

- 80 Indian Country Jails

- Women are the fastest growing incarcerated population in the United States.

- The southern states are the leaders of mass incarceration in the US.

- Crime rates have been dropping but incarceration rates are somehow going up.

- Youth are being increasingly locked up for offenses that are not even crimes:

- 6,600 youth behind bars for technical violations of their probation, rather than for a new offense.

- 1,700 youth are locked up for “status” offenses, which are “behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility.”

- Nearly 1 in 10 youth held for a criminal or delinquent offense is locked in an adult jail or prison and most of the others are held in juvenile facilities that look and operate a lot like prisons and jails.

- People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population.

Looking at the “whole pie” opens up new conversations. These conversations should challenge reflexive policy making, money bail practices, pre trial detention rates, etc. The numbers are astonishing and it is critical that these conversations happen more often to spark a much needed change in the justice system.

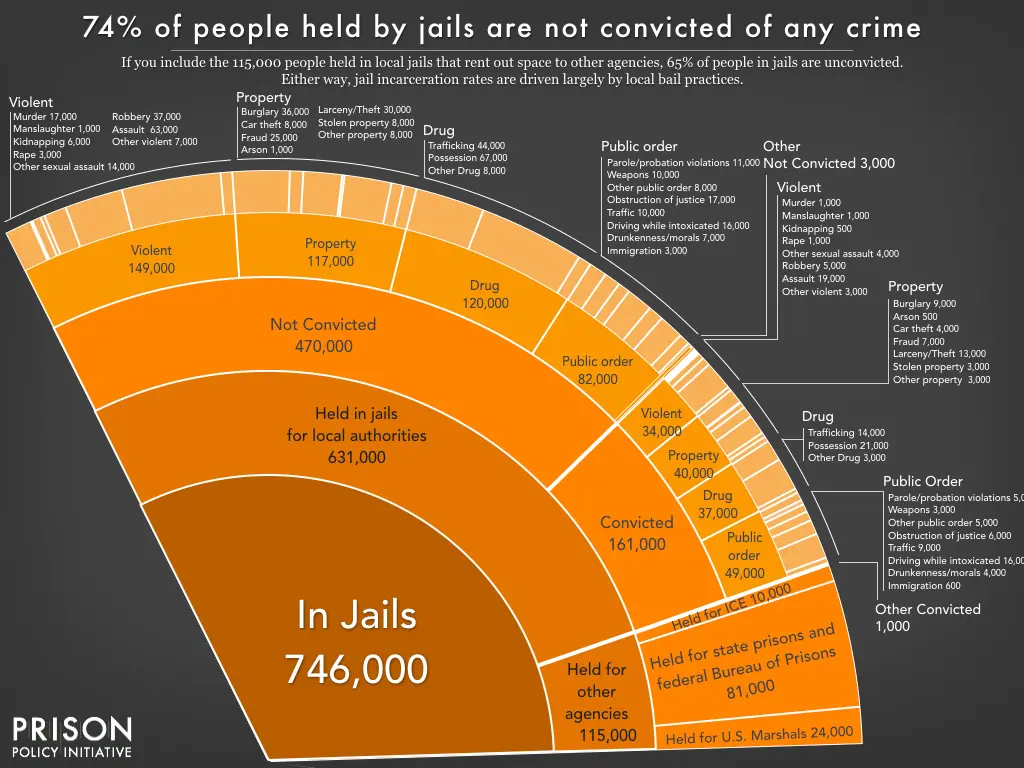

Convicted vs. Non Convicted

The difference between the totals of those convicted and those not convicted (but in jail) is staggering. Out of 746,000 people in jails, only 161,000 have actually been convicted of a crime. 585,000 of those people have not been convicted but are imprisoned. This data makes the statement “Innocent until proven guilty”, laughable.

Race, Immigration, and Poverty

Poverty is strongly correlated with multiple arrests. Nearly half (49%) of people with multiple arrests in the past year had individual incomes below $10,000 per year. In contrast, about a third (36%) of people arrested only once, and only one in five (21%) people who had no arrests, had incomes below $10,000.

The criminal justice system punishes poverty, beginning with the high price of money bail: The median felony bail bond amount ($10,000) is the equivalent of 8 months’ income for the typical detained defendant. As a result, people with low incomes are more likely to face the harms of pretrial detention. Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth, creates debt, and decimates job opportunities.

Despite making up only 13% of the general population, Black men and women account for 21% of people who were arrested just once and 28% of people arrested multiple times in 2017. This is partly reflective of persistent residential segregation and racial profiling, which subjects Black individuals and communities to greater surveillance and increased likelihood of police stops and searches. In addition, Black defendants generally receive longer sentences than their white counterparts for the same crime.

One out of every three Black boys born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime, as can one of every six Latino boys—compared to one of every 17 white boys.

https://www.aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/mass-incarceration

11,100 people are in federal prisons for criminal convictions of immigration offenses, and 13,600 more are held pretrial by the U.S. Marshals. The vast majority of people incarcerated for criminal immigration offenses are accused of illegal entry or illegal re-entry — in other words, for no more serious offense than crossing the border without permission.

Another 39,000 people are civilly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) not for any crime, but simply for their undocumented immigrant status. ICE detainees are physically confined in federally-run or privately-run immigration detention facilities, or in local jails under contract with ICE.

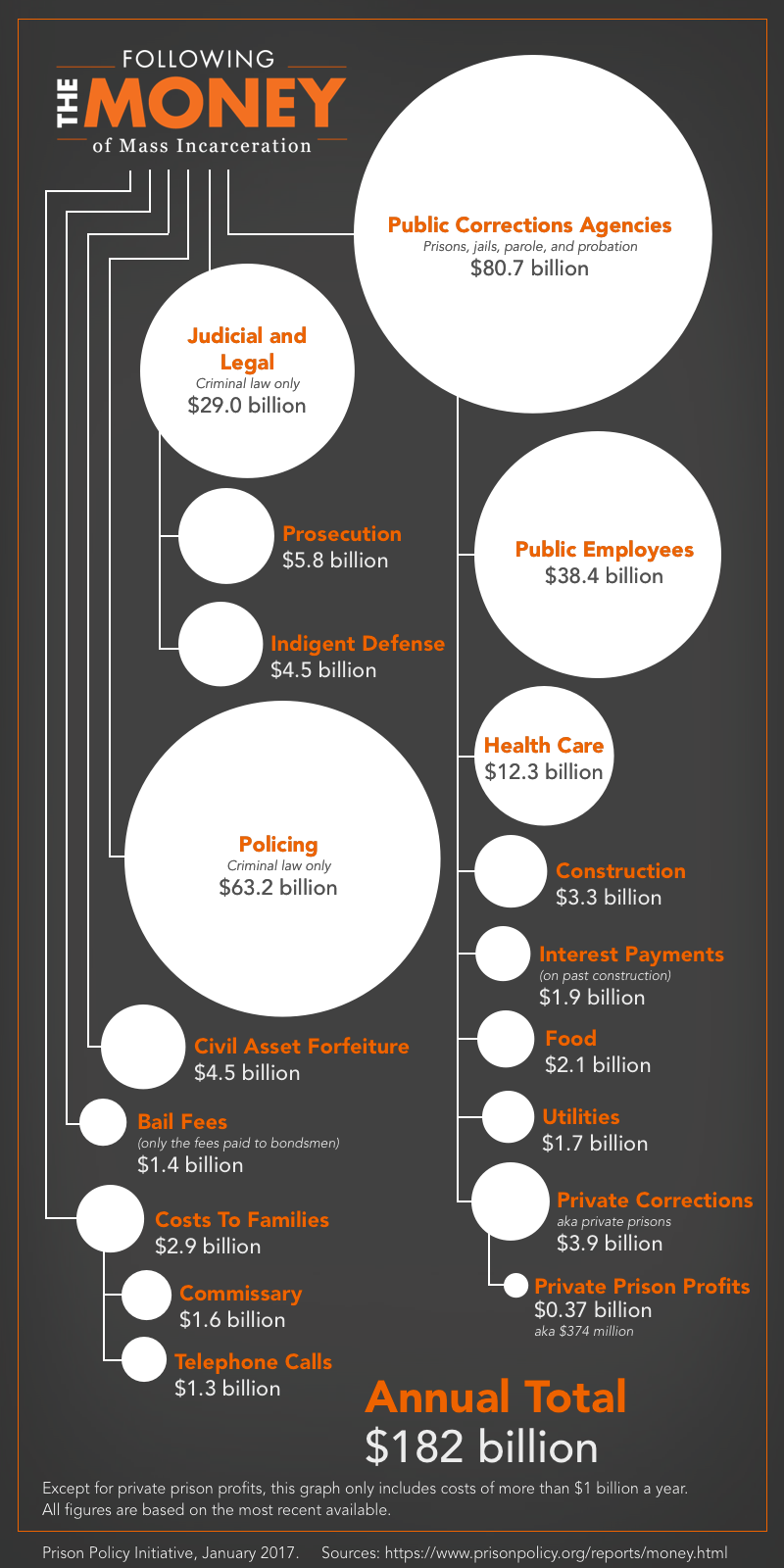

Cost

Commissary

Per-person commissary sales for the three sampled states amounted to $947, well over the typical amount incarcerated people earn working regular prison jobs in these states ($180 to $660 per year).

Not surprisingly, food dominates the sales reports; prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food. Another leading problem with prison food is inadequate nutritional content. While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed. Snacks and ready-to-eat food are major sellers, which is unsurprising given that many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest — if not only — alternatives are ramen and candy bars.

It’s a myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities.

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/commissary.html

In FY 2016, people in Massachusetts prisons purchased over 245,000 bars of soap, at a total cost of $215,057. That means individuals paid an average of $22 each for soap that year, even though DOC policy supposedly entitles them to one free bar of soap per week. Or to take a different example: the commissary sold 139 tubes of antifungal cream.

Accounting for gross revenue of just $556, the commissary contractor is obviously not getting rich selling antifungal cream, no matter the mark-up—instead, the point is that it’s hard to imagine why anyone would purchase antifungal cream other than to treat a medical condition. Yet Massachusetts has forced individual commissary customers to pay for their own treatment, at $4 per tube, which can represent four days’ wages for an incarcerated worker.

The other thing to keep in mind when comparing commissary prices to the free world is that people in prison have drastically less money to spend. So, while $1.87 may sound like a fair price to pay for a month’s worth of dental floss, the transaction feels very different from the perspective of someone in a Massachusetts prison who earns 14 cents per hour and has to work over 13 hours to pay off that floss. Or, to consider a different scenario: the average person in the Illinois prison system spends $80 a year on toiletries and hygiene products — an amount that could easily represent almost half of their annual wages.

Tax Payers

Our prison system costs taxpayers $80 billion per year. This money should be spent building up, not further harming, communities. Investment, not incarceration, is how we improve safety.

- Feeding and providing health care for 2.3 million people — a population larger than that of 15 different states — is expensive.

- Specialized phone companies that win monopoly contracts and charge families up to $24.95 for a 15-minute phone call.

- Commissary vendors that sell goods to incarcerated people — who rely largely on money sent by loved ones — is an even larger industry that brings in $1.6 billion a year.

- Not only has the imprisonment of the elderly driven up the incarceration rate, but it’s actually made prison much more expensive — because elderly people tend to require more health care. According to the Washington Post’s Sari Horwitz, the typical cost of a federal prisoner is about $27,500 a year, but older inmates cost nearly $59,000 each year.

“Jail Churn”

Every year, over 600,000 people enter prison gates, but people go to jail 10.6 million times each year. Jail churn is particularly high because most people in jails have not been convicted. Some have just been arrested and will make bail within hours or days, while many others are too poor to make bail and remain behind bars until their trial. Only a small number (about 160,000 on any given day) have been convicted, and are generally serving misdemeanors sentences under a year.

At least 1 in 4 people who go to jail will be arrested again within the same year — often those dealing with poverty, mental illness, and substance use disorders, whose problems only worsen with incarceration.

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html

Sentencing and Prosecution

Practically all crimes resulted in longer prison sentences after the 1980s. One particularly harsh form of sentencing was the “three-strikes” laws, which force people to serve 25 years to life after they’re convicted of any third felony. Lawmakers also passed “truth-in-sentencing” laws that require inmates to serve most of their prison sentences — typically 85 percent — before qualifying for parole.

The “massive misdemeanor system” in the U.S. is another important but overlooked contributor to overcriminalization and mass incarceration. For behaviors as benign as jaywalking or sitting on a sidewalk, an estimated 13 million misdemeanor charges sweep droves of Americans into the criminal justice system each year (and that’s excluding civil violations and speeding). These low-level offenses account for over 25% of the daily jail population nationally, and much more in some states and counties.

The problem isn’t just longer prison sentences. As a result of “tough on crime” policies, more people are also being admitted to prison. Since at least the 1990s, prosecutors have increasingly filed more charges for each arrest. So when someone was arrested by police, the prosecutor was generally more likely to file charges against that person in the 2000s than he or she was in the 1990s. This is one of the reasons — if not the reason — that admissions into prisons increased in the past few decades.

Criminologist John Pfaff cited several possible explanations for the trend, including political incentives to appear “tough on crime” and punitive policies strengthening prosecutors’ ability to file charges. Whatever the cause, prosecutors now play a big role in driving mass incarceration.

Voting

Most states don’t let people in prison, on parole, or on probation vote, and 10 limit at least some felons from voting after they’ve completed their sentences, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. As a result, more than 6.1 million Americans won’t be legally allowed to vote due to their criminal records in 2016.

Several states prohibited 5 to 11 percent of their electorate from voting. And since black Americans are likelier to go to prison, this had a disproportionate impact on the African-American electorate — leaving more than 20 percent of black voters in Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia legally banned from voting.

How can we fix this?

Frequently arresting, jailing and re-jailing people who pose little public safety risk has immediate moral and fiscal costs. These costs are compounded as underlying medical, financial, educational, and mental health needs are exacerbated by arrest and detention. To break this cycle, policymakers at the state and local level should:

- Redirect taxpayer dollars from jails to expand access to health services.

- Invest in community-based mental health care and treatment for substance use disorders, which can prevent criminal justice involvement in the first place.

- Counties should provide evidence-based mental health and substance use disorder treatment in jails, including medication-assisted treatment, and connect people with medical care and health insurance upon release to ensure their treatment is not disrupted.

- Connect people with social services.

- Expand job training and placement services, educational opportunities, and financial assistance for low-income individuals.

- Expand social services for people with unstable housing, focusing on “Housing First.” This approach acknowledges that stable homes are often necessary before people can address unemployment, illness, substance use disorder, and other problems.

- Police should issue citations in lieu of arrests, which allow defendants to wait for their court date at home without having to go to jail or post money bail. And local governments should to be sure to link defendants to pretrial services to ensure they make their court date.

- States should reclassify criminal offenses and turn misdemeanor charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions.

- States and counties should create pre-arrest diversion programs so people with mental illness and substance use disorders can avoid arrest altogether and be diverted directly to appropriate treatment and services.

- When people with substance use disorders and/or mental illnesses are arrested, states should make treatment-based diversion programs and other harm reduction strategies the default instead of jail. States should ensure their diversion and harm reduction programs are fully funded.

The Hard Questions

- Are state officials and prosecutors willing to rethink not just long sentences for drug offenses, but the reflexive, simplistic policy making that has served to increase incarceration for violent offenses as well?

- Do policymakers and the public have the stamina to confront the second largest slice of the pie: the thousands of locally administered jails?

- Will state, county, and city governments be brave enough to end money bail without imposing unnecessary conditions in order to bring down pretrial detention rates?

- Will local leaders be brave enough to redirect public spending to smarter investments like community-based drug treatment and job training?

- How can elected sheriffs, district attorneys, and judges — who all control larger shares of the correctional pie — slow the flow of people into the criminal justice system?

- Given that the companies with the greatest impact on incarcerated people are not private prison operators, but service providers that contract with public facilities, will states respond to public pressure to end contracts that squeeze money from people behind bars?

- Can we implement reforms that both reduce the number of people incarcerated in the U.S. and the well-known racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system?

The data shows there’s no correlation between imprisonment rates and crime, suggesting that states can bring down their prison populations without seriously risking public safety.

https://www.vox.com/2015/7/13/8913297/mass-incarceration-maps-charts

650,000 men and women nationwide returning from prison to their communities each year, face nearly 50,000 federal, state, and local legal restrictions that make it difficult to reintegrate back into society. Rehabilitation should be our goal so that those who have completed their sentences, have a greater potential to thrive when released.

Rather than incarceration, which diminishes economic prospects, public investments in employment assistance, education and vocational training, and financial assistance would help mediate the conditions that lead marginalized individuals to police contact in the first place.

Do Yourself A Favor

The Night Of

After a night of partying with a woman he picked up, a man wakes up to find her stabbed to death and is charged with her murder.

The Staircase

The high-profile murder trial of American novelist Michael Peterson following the death of his wife in 2001.

Blindspotting

While on probation, a man begins to re-evaluate his relationship with his volatile best friend.

No Comments